|

Memoirs of Reg Bulled

The Road From Freedom To Captivity

|

|

|

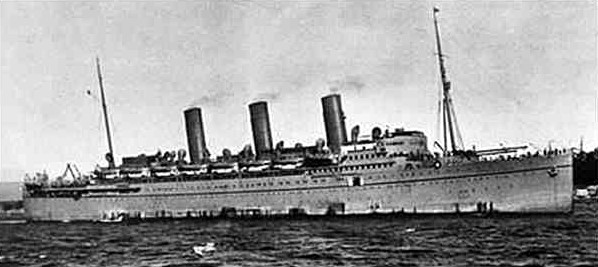

Empress of Asia

|

|

As I stood by the rail of the troopship “Empress of Asia” it was with a sense of excitement tinged with fear that I considered my immediate future. We had left England on October 21, 1941 bound for the desert. It had been a hectic few days prior to sailing as 13 of us were sent from Catterick Camp to join a unit in Stourbridge on the Wednesday afternoon. We travelled all night and finally arrived there at breakfast time the next morning. We found the unit all kitted out and waiting shipment out to the desert so we enquired of the C.O. as to our position. He informed us we would be going with them, when told we had no tropical kit neither had we had any embarkation leave he became angry with us, as if it was our fault. Apparently the powers at Catterick had sent the wrong men, they should have sent men ready to sail. We suggested that he phoned Catterick and inform them of their mistake and suggest they sent 13 others all kitted out. He said he didn’t have time for that even though if he had acted right away the correct men could have been there the next morning. Instead he ordered us to spend the day collecting all our tropical kit and the evening marking it with our name and number.

The next morning, when our replacements could have been there, he sent us home on 48 hours embarkation leave. I managed to send a telegram to my parents and arrived home at 7 o’clock on the Friday evening and had to leave again at 7 a.m. on Sunday in order to arrive back before midnight. I was to have been married but had no time for our wedding as the Registry Offices were closed for the weekend. We arrived back on Sunday evening and spent the next day doing absolutely nothing. On Tuesday morning we paraded with all our kit, and marched to the railway station. From there we went, by train to Liverpool, where we boarded our troop ship. What a rush! Less than one week from receiving news of our posting we were on a ship leaving England.

The first land we saw was Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, having lost our English naval escort to be replaced by an American one. In Halifax we transhipped onto American luxury liners fitted out as troopships and after three days there we left with an American escort (Convoy William Sail 12X) and sailed down to Trinidad where we took on fresh water and supplies.

|

|

|

Convoy William Sail 12X

|

|

On its way to Singapore

|

|

From there we sailed down to Cape Town, South Africa. Here we stayed for 3 days. While there we heard of the sinking of the ‘Prince of Wales’ and the ‘Repulse’; also that Japan had declared war on the allies. One brigade was immediately sent to Mombassa for a few days and then straight out to Singapore, the rest of the Division was sent to India for a few weeks of wasted time, then shipped out to Singapore. Now I found myself looking, not at the desert, but the lush tropical foliage of Sumatra on one side and Malaya on the other. What a farce, all our equipment was coloured for use in the desert and now we were going to the jungle!

Being completely unable to fathom the thoughts of the higher ups - they even insisted on us learning map reading in French every day - I went below and sat beside an opening in the side of the ship. Suddenly sirens sounded and we looked out and saw some planes coming toward us from the direction of Sumatra We naturally thought they had to be ours coming out to protect us the rest of the way into Singapore. When we saw some black dots falling from the planes we realised how wrong we were and when we saw the fried egg signs on the sides of the planes we knew we were being attacked. Luckily they missed us, one stick of bombs falling on either side of the ship. We were told the planes were coming back from a bombing mission on Sumatra and that was all the bombs they had left. Lucky for us! Where our officers got this information from, or why the planes were returning to base with unexploded bombs was anyone’s guess. Once again we witnessed the short-sightedness of our officers; all we had to fight off an enemy attack with was one Lewis machine gun on each side of the bridge and an anti-tank gun lashed down at the rear of the ship. All our rifles and other guns, with all the ammunition, were safely locked away in the bowels of the ship and there they stayed. I guess the senior officers thought we would be safely in Singapore harbour before we could be attacked again.

How wrong they proved to be once again. We were on an ancient boat that could not keep up with the rest of the convoy so we were left behind like sitting ducks after the attack. The ship was an ancient coal burner with no refrigeration. What sort of mentality would send men out to the tropics in such a ship? It didn’t take long for all the fresh food to go bad and become full of maggots. The ship wasn’t fit to send animals in let alone human beings. To make matters worse the crew had mutinied after the first attack and refused to work in the stokehold, saying it was a death trap. Volunteers from among the soldiers did their best but we slowed down even more, so when the planes came back the next morning we had no hope and little or no defence. They rushed up a few machine guns and those men firing them did a Herculean job of trying to keep the Japanese planes away from us. As soon as one gunner was hit another would jump in and take his place. But it was all to no avail. They swept in, machine gunning and bombing us until we were hit.

The steering was put out of action so they had to drop the anchors to stop us from floating into the mine fields. That made our position hopeless. The whole of the middle of the ship was engulfed in flames, and after helping a few men out from the sick bay we made our way up onto the deck. Here we were under attack not only from the planes but the ammunition from our own guns that was going off with the heat of the fires. It wasn’t long before our colonel, as senior officer, ordered every man to abandon ship and wished us the best of luck.

They had tried to lower the lifeboats but the mechanism wouldn’t work so they cut the ropes and let the boats fall. Some sank quickly, the others just turned over. Ropes were flung over the sides and tied to the rail and we either had to jump into the water from the deck or slide down the ropes. As I bent to untie my boots I lifted my heart to God and repeated the verse in II Timothy “I know whom I have believed and am persuaded that He is able to keep that which I have committed unto Him until that day.” This was the verse that opened my spiritual eyes and brought me into a saving relationship with Jesus Christ at the age of fifteen. I now asked Him to keep me safe.

I went over the side and down the rope, jumping over the men clinging to the bottom of the rope, afraid to let go and trust their life jackets. I swam as much as I could to get away from the ship in case it went down. After a while I came to an overturned lifeboat and being just about exhausted, I clung on to it. I remember speaking to an officer who was nearby and telling him I thought that this should have been my wedding day; I shall never forget his reply “you’re better off where you are lad.” I didn’t agree with him then and after 57 years of marriage I know he was wrong.

Gradually I became aware of a lot of small boats that had come out from Singapore - like another Dunkirk - which were picking men up out of the water. I felt it would be only a short time before they saw me and came to my rescue. After a while I realised there were no other men around me, and worse still, no small boats. They hadn’t seen me on the other side of the upturned lifeboat. I prayed again, how I prayed! Then I saw a motor launch coming and I started to shout and wave my arms. Finally someone waved back at me and I thought everything was now alright. But when I looked again I was horrified to see the boat heading away from me, so I started to shout and wave again. There came a response from the launch; a man stood up and pointed in the direction they were heading. When finally they came back and picked me up I was told they had seen another man with nothing to hold onto so had decided to pick him up first. We were taken to a lighthouse and from there to an Indian destroyer where my badly burned hands were treated and bandaged and I was given a naval shirt and shorts to wear.

We were eventually landed on Singapore and taken to a barracks for the night. There I met another man from my section, Lance-Corporal Foster and the next morning we asked every driver who came in if he knew where our unit was. Finally, one driver said he had an idea so we jumped into the back of his truck and after a while he stopped and told us our unit was around there somewhere. There we were, two soldiers in naval clothes with no boots or socks, wandering around in a foreign land wondering which way to go. We started to walk until we came to a road going off to our left and I felt we should go up there. My friend didn’t want to and suggested we keep going in the direction we were going. I really felt we should turn up to our left. Why? I couldn’t explain except that it had to be God’s leading.

We had only gone a little way when further along the road we saw a soldier come out of a driveway and turn toward us. How we shouted with excitement as we realised the man was our own section sergeant, Phil Hutt; we had found our section! I had asked God to take care of me and He had answered. When our sergeant recognised us he ran and hugged us, we were the only two men missing from the section. He said we had better rush down to Brigade HQ and correct the list of survivors. When we got there we were told the last messages had already left Singapore and there was no way the list could be corrected; so we knew we would be reported as missing in action. It was a very sobering and worrying thought, and I wondered how my loved one, who was supposed to be enjoying our honeymoon with me, would take the news. They had no idea even where we were. I thought also of my parents and sister, and the question crossed my mind - would I ever see them again? I prayed God they would never give up hope and that it would be His will that one day we would be reunited. I wonder how I would have felt if I had known that reunion wasn’t going to be for another 4 years!

Things began to move fairly rapidly after that. During the day we were subjected to bombing raids, but when the Japanese came they dropped all their bombs in one go, so if you got through that raid safely you knew you were safe to go about your duties without fear until the next raid. Also, the Japanese never seemed to bomb at night, giving some weight to the myth they couldn’t see in the dark. We always knew which way the Japanese were coming, the same directions our planes were going. Our planes were only being used as spotters and were so slow they had to get away quickly.

It was terrifying to be in one of those raids. I remember one time some of us were walking along an open road when the planes came over, machine gunning and bombing. We all dived head first into the large open drain at the side of the road, but one man was not satisfied to lie at the bottom of the ditch and wait until the raid was over, he wanted to watch the action. He stood up and that was the last thing he ever did on this earth. The futility of it; a life thrown away just because he couldn’t overcome his curiosity.

Our medical orderly had no drugs, bandages or medicines but eventually found a first aid post manned by some young Chinese; they cleaned my wounds and gave me fresh dressings. I visited them twice more before we were ordered to embark onto truck which took us to an airfield on a small river inlet.

Some of the men went scrounging as we realised there were no RAF types around and came back and said the airmen had evidently left in a great hurry as they had left their breakfast half eaten and their mail beside their plates. Also, all their guns and ammunition had been left behind. It certainly didn’t make us feel too good knowing that the RAF and the navy had abandoned us. We were led to positions on the bank of the river, amongst trees which had all their tops blown off by mortar shelling. We were told no talking of any kind as the Japanese were on the other side. It was ridiculous; here we were, an anti-tank regiment with a couple of men from the Royal Corps of Signals, acting as infantry. To make matters worse, we were given rusty old rifles and loose ammunition with no bandoliers or clips to carry them in. What a mess! This was the situation Churchill had sent a whole division into as lambs to the slaughter. It was so obvious that there was absolutely no hope. Malaya had fallen by the time we had arrived and the Japanese were massing to invade our island. I was worried in case my white bandages would show up too plainly in the dark so decided to take them off, which subsequently I realised was not a very bright idea.

The night passed without incident and the next morning a dispatch rider came roaring up to the colonel and told us we had to get out immediately as they were going to blow up the airfield. We jumped on whatever truck we could. A group of us rode on top of a loaded ammunition truck. As we left, we passed gun emplacements manned by Indian troops who were laughing and joking; we thought they were very brave but later found out that when the Japanese invaded, these very men had turned their guns on us and joined the enemy.

There are many things and occasions that stand out in my memory and that ride back to Singapore City is right up there towards the top. The enemy planes kept coming over very low and strafing our small convoy. When this happened you remembered you were on the top of an ammunition truck and certainly did not waste any time getting off as the driver pulled off to the edge of the road, and sought protection in the ditch. Finally our journey ended in a small plantation just outside the city limits. Here I was detailed to man a field telephone for an infantry officer, a “one-pipper”, who had established himself in an underground air raid shelter. I thought this was a brilliant idea until I realised that he was there because he was scared stiff and would not leave the shelter even to get his meals. He wanted me to get them for him but I figured I had enough to do carrying my own back and dodging mortar shells without worrying about his. We wondered what hope we had if this was an example of what we could expect from our officers. These are the same ones who swaggered around the decks with their one pip and acted as if they thought they were field marshals.

On the Sunday, around noon, I received a message that all officers were to report to the headquarters immediately. My officer was nearly in tears at the thought of leaving the shelter and I do believe he would have refused to go if I hadn’t told him he would be court-marshalled if he didn’t. When he came back his face was drained of all colour and I realised that some drastic decisions had been made. He said “we are surrendering this afternoon; we have to lay down our arms at 4:00 p.m.” I couldn’t believe my ears, what had happened, the mighty impregnable fortress of Singapore falling to the enemy in just a few days. We learned that the brass had always maintained that Singapore could only be attacked from the sea, so subsequently the great 20-inch naval guns were all pointed out to sea and could not be turned to cover our back door when the Japanese came down through Malaya instead.

To us late comers to the island it seemed as if our regular officers, who had been there for a few years, were not taking the situation seriously enough. They were so sure that the only way Singapore could be attacked was from the sea and our big guns would win any battle from that direction. Chaos seemed to reign supreme; officers and civilians still danced on the brightly lit lawns of Raffles Hotel while bombs fell on the city. They seemed to have no idea for defence of the coast around the causeway; they had been too used to living easily, lulled in the belief that Singapore was an impregnable fortress. The Japanese, in a few short days, expelled that belief forever.

We laid down our arms at 4 p.m. and, except for the odd shell, silence reigned. Ten days after landing on Singapore Island we were P.O.W.s, never having seen a Japanese soldier. We sat there, alone with our thoughts. What a mess Churchill had made - sending a whole division, without trucks, guns or ammunition, to defend an island already overrun with too many troops but desperately in need of guns and supplies. If only Churchill could have heard what the men thought of him and the blunder he had made. He had not only sent us into slavery but had extended the war in the desert by not letting our division go there. As planned. But this was not the only blunder he made; just ask the Canadian troops who were sold into captivity by him what they think. I believe that at that time Mr. Churchill had sealed his eventual defeat in parliament, no-one would vote for him or his party.

No-one slept very much that night, nor did they talk much, each man was alone with his thoughts and fears. We knew that in action the Japanese had not taken prisoners but had beheaded or bayoneted all of those captured, even when they had surrendered peacefully. Was this to be our fate as well? I went back in my mind to the events in my life since I had reached the age of fifteen years. First I met a young lady on the way to Sunday Bible Class. As soon as I saw her I knew, though I was young, that this was the girl I wanted to spend my life with. To say it was love at first sight sounds a little trite but nevertheless it was true, and as I look back over the years I know how true it was. She was a lovely person both outwardly and inwardly, a true Christian who lived her faith. It was through her consistent testimony that I felt the need to trust her Saviour, but I resisted for months until I was finally broken of my stubborn pride and asked Jesus Christ to come into my heart as Saviour and Lord. Now, in the dark of this night, I looked back in memory and realised how God had worked in my life to prepare me for the years of captivity. My girl friend and I had taken every opportunity to listen as men taught the Scriptures and how to live a triumphant Christian life. We had decided immediately that we had to tell others of the love of Jesus Christ, so being only young teenagers we became active in Sunday School work. We also attended Bible classes to give us a good grounding in the Word. Never for a moment did I ever dream how important this time of learning was going to be and what it would mean in my life. How we loved to sing the hymns and memorize them and portions of the Holy Scriptures. That was to be a great help to me in the next few years as all my possessions, including my Bibles and photographs went down with the ship.

Believing in the inevitable victory of the allies we felt that our time of imprisonment, if the Japanese decided that was to be our fate, was going to be very short. I thank God that He who knows the end from the beginning, wonderfully kept hidden from us our future. I don’t think many of us could have stood the shock of what was in store for us.

All through that night we realised the utter and total depravity of the Japanese soldiers as women continually screamed as they were being brutally raped by the conquering troops. Once the surrender had been signed, the Japanese high command had turned the city over to their troops to have their fun and relaxation. This they proceeded to do with utter ruthlessness. The next morning we saw, around the huts of the native workers, the corpses of women who had been savagely and continuously raped and then butchered. As we looked around the sight struck terror into our hearts. What sort of animals were these men! We believed that as POWs we would be covered by the Geneva Convention regarding the treatment of POWs. We were so na´ve!

Later that morning, as three or four of us were sitting at the side of the main road, we observed a truck being driven erratically up the road toward us. We all started to laugh and thought this soldier either didn’t know how to drive or else was drunk. Our laughter turned to silence as the truck came to a stop and a Japanese soldier jumped out and started to scream at us. He finally convinced us that he wanted our rings, watches and pens. I was the last one he came to and all I had was my engagement ring and he demanded that. I told him to get lost he wasn’t having it. He pulled out his bayonet, grabbed my wrist and let me know he was going to have the ring even if he had to take the hand with it. Prudently I decided to give him the ring, as what use was a ring without a hand! I could always get another ring but not another hand. So my last link with home and my fiancÚ vanished into the pocket of this unknown Japanese soldier. Our senior officer complained about this treatment and was told that if we could indicate the soldier involved he would be severely punished. What a joke, they all looked alike at that time to us.

Two or three days later we were told we had to assemble and march to a prepared prison camp at Changi. I shall never forget that journey. We had to carry everything we wanted to take with us including all our cooking utensils. As we marched through Singapore city, the streets were lined with the native population who laughed and jeered at the white lords and how they had fallen. They spat on us and beat us with bamboos. They were venting their hatred upon the white man who had kept them down for so long. They evidently believed the stories the Japanese had put out that this war was to make Asia for the Asians. I wonder how long it took them to learn the truth that the war was to make Asia for the Japanese.

We felt very humiliated and more than one soldier voiced the opinion that Churchill should be there to see what he had done to thousands of young men. The much vaunted impregnable fortress had fallen without one shot being fired from the big guns! How we wondered as we marched along what the future held in store for us. I was feeling even more miserable as my fingers that had been burned on the ship were had steadily become worse through lack of medical attention. Two fingers on my left hand were badly swollen and had become sceptic; they throbbed and burned without relief.

As we picked our way along the streets littered with debris and overturned and burned out cars, trucks and tramcars, the man in front of me brushed against a thick tram wire. As he passed it sprang back and hit my left hand hard. The agony of the blow was almost too much to bear, but immediately I became aware of a wonderful relief from pain. The blow had burst the blisters on my fingers and allowed the poison to run out. I am happy to say that was what was needed as my hand steadily got better after that.

It was a long journey; we had not had much sleep for three or four nights and had been existing on very little food, just a little bully beef and hard army biscuits. The Japanese had refused to supply us with any food at all so we just plodded along, putting one foot in front of the other, hoping we would soon come to the end of our journey, or be given a rest period. We were harried and beaten all the way by the guards. We who were at the tail end of the column were still on the road when dusk began to fall and we were halted near a park and told to spend the night there. The POWs had evidently been arriving too fast for the British officers to assign them sleeping spaces; it must have been a tremendous undertaking for them as they had had no warning or chance to inspect the camp. We didn’t argue but just put our packs down and fell almost immediately asleep on the grass without anything to eat or drink.

Early next morning we continued our journey and realised we had nearly reached the camp the night before. We came to an opening in the bamboo fence that was enclosing the camp area; as we marched through the gateway we hoped this was to be our permanent camp for the duration of our captivity. We were shown where we were to sleep, just enough room to lay out flat. There we sat, tired, aching and very hungry. It had been a sixteen mile march to Changi and for those of us not used to route marches it had been a long haul. As we sat there, a feeling of despair came over us as at last the reality of our position set in.

Did our families know we were prisoners? How much comfort it would have given us to know that they knew where we were and that we were still alive, but no-one could give us this hope. The Japanese had built this camp, or at least fenced in this area that consisted of some multi-storied concrete buildings, known as Roberts barracks, officer’s quarters and some neat little houses which had been the married quarters. Also, there were extensive areas for tenting. I was first given a bed space on one of the top floors of the barracks which was good as it afforded shelter from the burning heat of the sun. As we sat around we were painfully aware that we were being slowly starved to death - the hunger pains never left us. We wondered how long our captors would keep us in this condition before they decided to feed us. They soon let us know the answer. We were informed that all regiments carried rations and water for a long period so they would not give us anything until that period had ended. They refused to understand that their troops had confiscated all of our ration and water trucks, either in action or after the capitulation.

Next Chapter

Life in the Camps

|