|

Friday, August 11, 1995

Daily Mirror

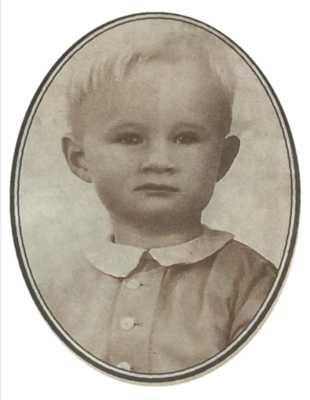

Picture that gave me the will to survive

It is an old little photograph,. Two smiling women and a small boy with his legs through the arms of a wollen cardigan.

But for four hellish years the snapshot was Jim Bradley’s single link with reality as he suffered appalling cruelties at the hands of the Japanese.

Wrapped up tightly and never far from his heart, it is a picture of his lovely young wife, Lindsay, their blonde-haired son, Roger, and Jim’s mother-in-law.

It gave jim the strength to overcome suffering that was among the worst experienced by any soldier in the second World War.

Fifty years later Jim holds the photo as he sits in the living-room of his home in Midhurst, West Sussex, quietly relating experiences more terrible than anything in Bridge Over The River Kwai.

The hastily snapped picture of a family picnic shows Roger after he had fallen in the river and had been dressed in his mum’s cardigan, his legs down the sleeves. But to Jim, who believes his is the only man alive to have escaped a Japanese prisoner of war camp, it was his whole world.

His wife’s warm smile, as he lay starved, exhausted and desperately sick in an Asian jungle, meant home to him, it meant normality.

A tall, spare man, remarkably fit for his 84 years, Jim says softly. “I was absolutely determined that one day I would get back to them.”

Jim Bradley was the man who shook the hand of repentant death camp tyrant Hiroshi Abe in Yokohama two weeks ago.

Listening to him tell his harrowing story, it is hard to understand how he ever found it in his heart to forgive.

A Cambridge engineering graduate, Jim was a lieutenant in the Sappers when he arrived in Singapore in 1942.

After 30 days of action the island fell and Jim, with hundreds of other Allied troops, was marched off to the infamous Changi jail.

Compared to what was to happen later, Changi was not too bad. It had been a British Army base and the men were able to play cricket and hold concert parties.

The big problem was lack of food, the rations consisting almost entirely of weevil-infested rice.

After 14 months, 7,000 already weak and emaciated men - half of them British, half Australian - were sent ro work on the railway of Death.

“For five days we were packed into closed rice trucks.” says Jim. “There was only enough room to sit with your knees drawn up. We all had dysentery but there were no washing or latrine facilities.”

They arrived at a filthy, stinking camp, where, after one day’s rest they were ordered to march for 20 days through 300 kilometres of narrow tracks through the jungle.

“We marched by night, trying to carry the sick. It was pitch black and sometimes we staggered along knee-deep in water.” says jim. “Many men died on the way. During the day we lay down where we could and tried to rest. All we got was rice and hot water with bits of onion floating in it twice a day.”

“One place was infected with cholera and the ground was all fouled. We asked for spades to clear it up but the Japanese just snapped: ‘Use your hands’. Of course we got cholera too.”

“When we arrived at Sonkurai there was no time off to recover. We had to work 15 hours a day in the pouring rain, up to our waists in water to build a bridge.”

“people were beaton with barbed wire or bamboo canes if the Japs thought they were not working hard enough, or were made to stand in the sun or rain for hours, holding a stone above their heads.”

“Over 20 people a day were dying of cholera - i was the only officer revealed to be a cholera carrier, so I was ordered to take 70 or 80 others with me and start an isolation camp.”

“ The place chosen had been a cremation area for coolies and was littered with half-cremated bodies. It was my job to cut wood for the funeral pyres for our dead.”

“Every morning I would count the bodies outside the hospital and again at midday to see how much wood was needed.”

“But cholera strikes so quickly that sometimes man who were cutting wood with me in the morning were lying on their pyres at night.”

Jim expected to die. he had all the symptoms of cholera as well as amoebic dysentery, malaria and beri-beri.

But he hung on and when Colonel Mike Wilkinson asked him to join an escape party, it seemed a matter of merely choosing which way he would meet his death.

“It was still a difficult decision. I didn’t know if we could get out, or if we could survive in the jungle once we had,” said Jim.

“I knew all escapees were bayoneted or shot on sight, but I was very unlikely to live anyway and I thought this way we might have a chance.”

Men began spiriting away rice and tins of fish which Jim hid in his cholera-infected camp.

Someone made a crude map and Jim had a compass built into his water bottle.

They reckoned it would take three weeks to reach the coast. What they didn’t know was that their route would take them across a mountain range with peaks reaching 4,000 feet.

Ten men joined the escape party, each one agreeing that, if he fell sick, the others were to leave him to his fate.

On the night of july 5, 1943, they crept out of the evil-smelling camp and set their faces west.

“It rained all the time, The tangled bamboo grew 40 feet high and we had two axes to slash through it. It was completely exhausting. Some days we only progressed 300 yards. Our food was getting less and less all the time. We had a little rice and maybe half a sardine pr pilchard every day. our biggest fear was leeches. If you pulled them straight off you left the head and jaws embedded which could turn septic. But we ran out of matches to burn them off.”

“One morning we found a man missing. he had gangrene, had become delirious and wandered off. We went back along the track, but couldn’t find him.”

They lost four more on the way, including Jim’s Colonel.

“He was a regular soldier who weighed 19 stone when fit, and he lost so much weight it proved too much for his heart.”

There was a moment when Jim felt he could go no further.

“It was when my colonel said he couldn’t go on. I felt I would stay with him. I had a lot of pain rounf my heart too. But he died in the night, so O decided I may as well go on.”

After eight weeks - the last three of them with no food at all, only water - the five survivors reached the Ye river and spent three days building a raft to take them to the coast

Soon after they set sail, they plunged down a gorge and the raft was smashed to pieces.

Jim had his photograph, wrapped in his waterproof cape, in his pack slung round his neck. It survived the soaking.

When all five had clambered from the river they met two Burmese hunters, who sold them to the Japanese.

“We knew what they were doing but we were too weak to da any more, “ says Jim.

Three days of “rough questioning” followed. Jim believes the only thing which saved them from an instant bayoneting, was that the Japanese had no idea where they had come from.

The escapees were locked in a 6ft by 6ft bamboo cage and put on display at camps all along the railway as a warning.

Fed on one ball of rice in the morning and one in the evening, they were taken out for “questioning” - with the aid of a leather belt.

One morning a British soldier whispered to them that they were to be executed that afternoon. As senior officers gathered to witness their deaths, Jim’s thoughts were: “The sooner the better.”

He was absolutely finished - but unknown to Jim, Colonel Cyril Wild, a fluent Japanese speaker, had reduced the Japanese commandant to tears by arguing that he would bring shame upon the Emperor by executing “these brave men”.

Weighing less than six stone and desperately ill, Jim was then taken to the place he describes as “the worst of all” - Outram Road jail in Singapore.

“ I was put in a bare cell in which an electric light burned all night, “ he says. “There were two planks for a bed, a wooden block for a pillow, one blanket, a bucket and a slit in the door through which they passed rice and water twice a day. I had to sit at attention all day and shout my number out to the constant roll-calls. I got so weak I kept passing out. They had ways of testing if you were faking, like tickling your foot with a feather. I have still got a mark on my arm where I tried to break it in a bid to get taken to hospital. I put my arm on the block and hit it with a plank. But I hadn’t the strength to wield the plank hard enough.”

After eight weeks of torment Jim was so ill he was taken back to Changi where he remained for the rest of the war.

Going Home: Emaciated but jubilant Allied troops as the gates of hell are finally opened

Ask Jim what was the worst moments and he chews his lip, unable to answer. The poignant ones are easy to pinpoint. The moment he embraced Lindsay on the station at Holyhead, North Wales. The one little later when they stood, hand in hand, looking down on a sleeping Roger. Lindsay had heard nothing of Jim for three years. She only knew he was alive when a message was picked up on the radio - jim still doesn’t know who sent it - saying “Tell Lindsay, Jim is OK”.

Jim weeps a little. Someone else’s pain, someone else’s longings, bring the tears.

In and out of hospital for treatment on hi tropical diseases, unable to hold down an engineering job because of migraine, he never spoke of the horrors he had seen - but they visited him in the night with terrible vividness.

“I had nightmares for the first 35 years, “ he says matter-of-factly.

In the bamboo hell of Outram Road he had promised himself that if he got out alive he would work on the land. He turned to farming, eventually buying his own fruit farm.

Roger followed jim to the same public school and the same college at Cambridge. Now 58, he and his wife live close to Jim.

It was Jim’s second wife, Lindy, whom he married after Lindsay died in 1969, who persuaded him to write about his experiences.

The writing worked as an exorcism. The nightmares have dwindled to a few a year.

Now he has shaken the hand of the man who terrorised the prisoners at Sunkurai. Hiroshi Abe was in tears as he told Jim he had never forgotten the sight of him burning the bodies of his comrades.

“I had heard that this man truly regretted what he had done and felt the Emperor should have been indicted as a war criminal. I thought it was my duty to shake his hand,” says Jim.

“I was never bitter as others were. I felt I would never want anyone else to go through what I had, and the way to stop it is to have peace.

|

|

|

|

Life Saver: Baby Roger

|

Young Soldier: Jim Bradley

|

|

“I hated their guts during the war. But if I went on hating, there would be peace for the next generation.”

Appalling Cost of Far East Conflict

- By the end of the Second World War, the British had lost 335,000 people as a result of enemy action. The war had done so much damage to UK industry that registered shipping tonnage shrunk by 30 per cent.

- Nearly 300,000 PoWs were taken by the Japanese in the whole of South East Asia, but over 100,000 died before liberation.

- The Japanese took 270,000 prisoners from India, China and the Dutch East Indies. Many were forced to support the Japanese war effort and laboured on the infamous Burma-Siam railway.

- Of the 50,016 British troops captured by the Japanese 12,433 died in captivity.

- More than 24,000 Indian troops were killed in action, 64,354 were wounded, 11,754 were reported missing and 74,489 became PoWs.

- Around 800,000 Indian civilians perished in the fight for Burma when the Japanese invaded in 1941. Many died from exhaustion, starvation and disease.

- The 14th Army who fought in Burma - won 101 battle honours, more than any other single campaign. This total included 29 Victoria Crosses.

- By 1946 the survivors of the far East were nearly all home, but the British military involvement in the area was to continue for many decades.

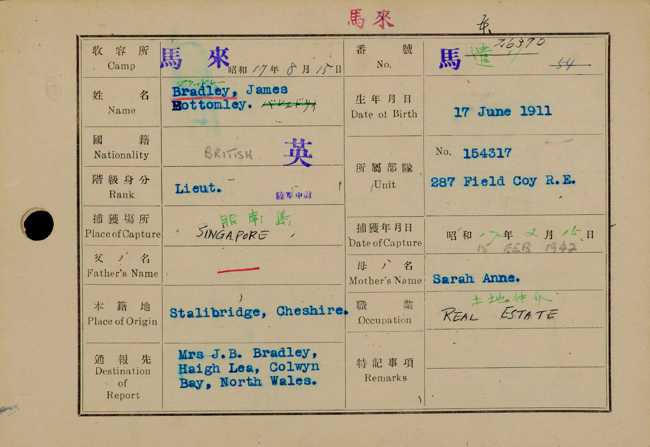

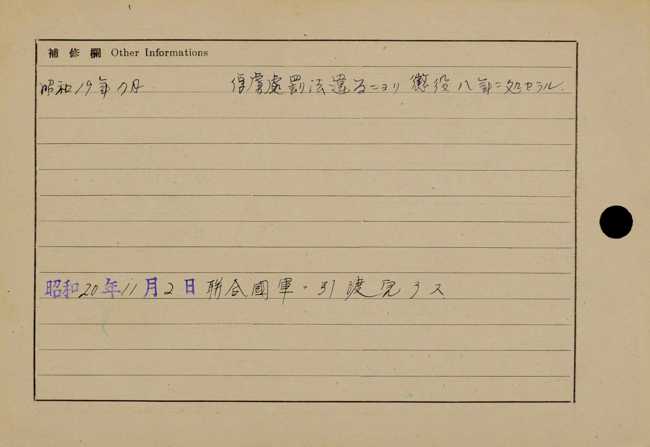

Added Information

Lieutenant James Bottomley Bradley, 154317, Royal Engineers, 18th Division

‘F’ Force to Thailand

Ex Outram Road Jail - 1943/12/21

Japanese Index Card - Side One

Japanese Index Card - Side Two

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Previous Page

|

Next Page

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|