|

1995

Eastern Daily Press

A hate that’s hard to forget

For many survivors of Japanese cruelty, forgiveness is still too difficult

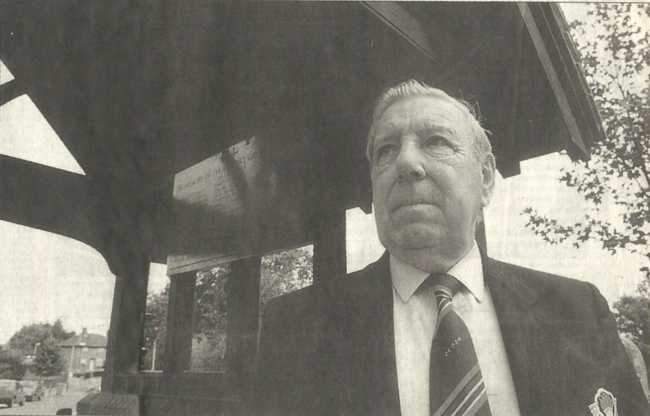

Maurice Rooney came home from the war with a burning hatred of all things Japanese.

Like so many other survivors of the wretched slave labour camps, he emerged after three and a half years of brutal captivity personally embittered by a degree of inhumanity which defied civilised comprehension and which had resulted in the unnecessary deaths of thousands of his comrades.

Among those he left behind in cemeteries scattered across Asia, from the malarial jungles of southern Burma to the shores of Japan itself, was his elder brother, an earlier victim of the notorious Railway of Death. Among those he left behind in cemeteries scattered across Asia, from the malarial jungles of southern Burma to the shores of Japan itself, was his elder brother, an earlier victim of the notorious Railway of Death.

“When I returned, “ he says quietly, “There was nobody who had more hate in their heart than I did. As far as I was concerned there was only one good Jap, whether it be man, woman or child, and that was a dead one.”

Such views were not unique. The tortured memories of a nightmare episode beyond the understanding of even the closest relative left deep psychological wounds which have been slow to heal.

Fifty years on, the former Norwich territorial , who passed his 21st birthday in Singapore’s crowded Changi prison camp, has come a long way down the path of reconciliation.

There have been obstacles along the way - most recent the decision of Prince Philip to attend the funeral of Emperor Hirohito which prompted him to return hi wartime medals in protest - but the anger has given way to a calmer rationale in which the demons of his past, while not exorcised, have been contained.

“I have nothing against the younger, post-war generation of Japanese, “ he explains. “But even now I could not cope with mixing with Japanese of my generation. If I see one of them in person or on television I literally go cold and my hair bristles. I wonder what he did during the war. Could he have been one of our brutal guards? I simply can’t handle it.”

Many among the dwindling number of men from the 18th East Anglian Division, who were taken prisoner when Singapore fell to the Japanese 53 years ago, will readily understand such feelings.

For them the 50th anniversary of VJ Day represents an uneasy milestone, conjuring up a wide range of emotions - from recollections of the relief and joy that accompanied liberation to the painful reminders of a living hell which, for some, has endured long after the peace.

Unlike the VE Day extravaganza when the desire to party gripped the nation, the mood inevitably is less of triumphalism than remembrance.

Gordon Buckley, a former sergeant in the Royal Norfolks from Pentney, near king’s Lynn, insists: “VJ Day is not a day of celebration as far as I’m concerned. My thoughts will be with those lads we left behind.”

Maurice Rooney reinforces this view.

“Parades are all right for the Desert Rats of the 8th Army and the Normandy veterans, “ he says, “They were victorious armies - we were not!”

As a fighting force, the ordeal of the 18th Division was almost unique among Britain’s army. Following a short-lived and disastrous campaign, they were compelled, through no fault of their own, to endure degradation, deprivation and, in too many cases, depraved maltreatment at the hands of their captors. Theirs was not a long march to victory, but a struggle for survival.

Almost a third of the 15,000 strong Division taken prisoner died in captivity. VJ Day spelled only salvation to the emaciated, disease-ridden survivors.

Maurice Rooney’s abiding memory of freedom was of standing by the rails of an American ship and watching as the island of Formosa, where he had toiled in the copper mines, dissolved into a speck on the horizon.

“I doubt whether many people can have experienced the joy and relief of that day, “ he says.

Others who were in jungle camps dotted throughout Thailand, recall wild celebrations. But many were too ill or weak from malnutrition to celebrate. Tom Eaton,, an ex-company commander in the 4th Royal Norfolks, president of the Norwich FEPOW branch and a former Lord Mayor, was in Changi when the war ended. He recalls: “ We heard the news on our secret camp radio but we were under strict orders not to reveal by sign or action that we knew they had surrendered until the indication came from the Japanese. When it did come, I think it’s fair to say that we had seen too much to be euphoric.”

And, in any case, the suffering did not end with the peace. Haunted by the recurring nightmares of their ordeal, many former prisoners struggled to make the transition to civilian life in a country where few appeared to understand or care.

Some returned to find their wives had deserted them. In many cases, loyal wives found their husbands altered beyond recognition.

For thousands of far Eastern PoWs a legacy of mental anguish and physical decline. hastened by their terrible experiences, has added a new dimension to a wartime tragedy.

While some retreated into an impenetrable shell others focused their anger into new campaigns: fighting for pensions from their own government and for greater compensation from the Japanese.

It comes as little surprise then, that few have found it within themselves to forgive the sins of their wartime oppressors.

Gordon Buckley, who survived the infamous Burma-Thailand Railway is forthright on the subject.

“I know there are some who say we should forget. “ he says, “but what happened to us is something we shall never forget or forgive.”

Such reactions remain the norm among ex-FEPOWs, but they are not universal. Ken Smithdale, a former private soldier in the 6th Royal Norfolks taken prisoner in Malaya, believes it is time to bury past animosities.

“I will never forget,” he said “but I am now 79. Do I continue to hold it against the Japanese for the rest of my life? Surely we have to stop somewhere.”

The recent Japanese earthquake brought home to him just how much his views have altered, “In spite of the beatings I received as a prisoner, I still found myself sympathising with those ordinary people who were suffering so much.”

“Of course, there have been times when I have felt aggravated by my memories of the past, but the mistreatment was only carried out by a certain number of Japanese and we have to come to terms with that.”

Another veteran of Changi, Bill Goodwin, who is currently organising a special service of remembrance in his home village of repps, adds: “As far as I am concerned, once the service is over I will not want to know any more about the Japanese. I will want to forget.”

The thorny issue of reconciliation remains a highly charged one and reactions to it are deeply personal.

Tom Eaton insists the matter can not be forced.

He spent his entire captivity in Changi after being badly wounded on the day Singapore surrendered, and he says, “ I never had any hang-ups over it. I had no nightmares. I bore no grudges. But it has to be accepted that there were many hundreds if not thousands of people who had such awful experiences of the Japanese that they can never forget and will never feel comfortable in the company of their former enemy. It has cast a shadow over their lives.”

All of this serves to underscore the emotional impetus behind the VJ Day commemorations in East Anglia.

In Tom Eaton’s estimation, no other wartime campaign or experience provoked such profound spiritual feelings.

“This emotional element is quite special and exceptional in that here we have people who went through three-and-a-half years of slavery and endured hardships which were unbelievable - so it’s inevitable that they have left their mark.”

However, he firmly believes that the media’s focus on the 50th anniversary has proved beneficial to many surviving PoWs.

“It has enabled a lot of people to unburden themselves and their sacrifices are being seen in a national context in a way which shows that they and their comrades who died have not been forgotten.”

Maurice, Reg, Arthur and many more FEPOWs who were members of the FEPOW Community helped me form a group which supported FEPOW Day to be held on August 15th. After 500 names were collected on a poll to the government, it was refused as it clashed with VJ Day. We still hold the day as FEPOW Day as it is now recognised by almost all FEPOW Associations and groups. This is the day of liberation and the day the FEPOWs could look back in remembrance of their lost mates. FEPOW Day and FEPOW family pins are available from http://www.fepow-day.org .

Ronnie Taylor - FEPOW Family

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Previous Page

|

Next Page

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|