|

FREEDOM LOOSENS THE MEMORY

Edwin Arthur Young

20th August 1945

Arrived at Gourock, Scotland at 5.30am, November 9th 1941 - a cold, misty morning, some sleet falling. Formed up on platform and after some twenty minutes or so delay we marched out of that cheerless station and boarded a ferry which was tied up alongside the quay.

Almost the first thing we learned was that the ferry would not take us out to our transport until 8am so we made ourselves as comfortable as possible down below on the deck and alternately dozed and chatted. We heard two more trains arrive at the station nearby and more troops came aboard.

It seemed an age before the engines began to turn over (and our stomachs somewhat as well for we had not breakfasted) and our ferry began to move. A few of us went up on deck but as the mist was still hanging we could see but little, two or three liners and a few smaller craft. After about 15 minutes run we drew up alongside one of the liners - ‘The Empress of Japan’ - which was to be our home during the next six weeks.

The ‘Empress’ was a grand liner of 26,000 tons and had been doing the C.P.R.’s Pacific run to Japan during the years immediately preceding the war. She was beautifully appointed and had been stripped but little so we considered ourselves to be very fortunate indeed. The main dining saloon seated a good thousand troops at one sifting and it was to this veritable amphitheatre, tastefully decorated in blue and gold, that we were conducted after being shown our berths or mess-decks and having dumped our equipment.

After the shortage of food in England, we were astounded at our first breakfast aboard! One was offered grapefruit (fresh) or porridge, to accompany which were large jugs of milk and basins heaped high with sugar; as many rashers of bacon and as many flied eggs as one could manage; bread or toast with marmalade and lashings of hot strong tea and coffee. That meal will, I think, live forever in my memory.

I will not dwell on it but will add that I could not face a lunch of roast pork, with all the trappings, which I might have eaten at 1 o’clock but not a scant two hours after breakfast.

During the next six weeks this high standard, both in quality and quantity of the food, was maintained and we were extremely grateful to the Chinese kitchen staff who were responsible. I had a chance later of inspecting the galley and was delighted with the cleanliness of everything therein. Spotless tables, chrome topped (or was it stainless steel?) rubber covered floors and everything covered up so that there was little or none of that greasy smell which one usually associates with the kitchen.

A little later I visited the bakery and saw literally and figuratively yards and yards of white bread going into the electric ovens, to emerge after a short while baked a delicious golden brown. Everyone aboard voted this bread to be some of the best that they had ever eaten.

Then a glimpse of things to come, way down at the bottom of the ship - the refrigerating chambers. Hanging from the ceiling and on the walls were chickens, sides of pork and turkeys (the latter for our Xmas dinner). All foods for the long trip were kept in that long room, stretching almost two-thirds of the ship’s length.

At first we were inclined to grumble at what seemed to be overcrowding on the mess-decks, for when the hammocks were slung there was only just room enough between hammocks for one to climb in. This was at first a difficult feat, many promptly falling out again on the other side but one soon acquired the knack. By day, with all hammocks neatly rolled and stowed, there was ample space to sit, recline or move about. After ‘blackout’ time the space was rather crowded because everyone was ‘at home’, either playing cards, ‘Housey-housey’, chess, dominoes, reading, writing, being musical as only soldiers know how, or just sifting. ‘Black-out’ restrictions, although very necessary, proved extremely trying, more especially after a week or so when we reached warmer climes.

We lay four days off Gourock while our convoy was forming, an irritating period for one of our comrades who could see his home from the ship! Many rumours went round as to when we would sail, culled from all parts of the ship, but most men were asleep when the turbines were started at 11.2 5pm on the night of 12th November and we began to move out into the Clyde at 11 .4 5pm. Does the old superstition of the number 13 apply to the sea as well? Apparently so.

By daylight next day we were out of sight of land and, although the sea looked rather rough, the ‘Empress’ rocked but little. Midmorning four destroyers raced up and crossed ahead of us, making a fine sight as they pushed sturdily through the waves with decks almost awash.

A short while later the remainder of our convoy came up with us, having left Liverpool the previous afternoon. We now numbered 15 ships in all, comprising 10 liners and 5 large cargo vessels. All were armed against surface raiders and aircraft and manning crews were obtained from the passengers’! Fortunately we did not see any enemy aircraft but, nevertheless, we were prepared.

It was my first convoy and, incidentally, my first long sea voyage so I had much both to see and to learn. I was amazed to find that, when I had my first glimpse of the convoy in the morning, all the ships seemed to be in the exact positions which they had occupied at dusk the previous evening and that after steaming in complete darkness throughout the night! Another optical illusion was that when one looked astern at the ships which followed, they all appeared to be sliding down hill behind us.

There was very little motion to the passage to the ships but one could gather some idea of the roughness of the seas by watching our escorting corvettes, almost on our horizon to port and to starboard. They did everything but sink, standing first on their bows then on their sterns, pitching and tossing like corks in a mill-race! How we ‘landmen’ felt for those poor souls aboard the corvettes but I expect the sea seemed almost calm to them. Perhaps their craft became subs. in really rough weather and submerged altogether!

Soon after midday we sighted land on the port side, our last view of Northern Ireland and our last sight of land for some days. On the fourth day out of Gourock we ran into bright sunshine and knew that we were passing the Bay of Biscay by the heavy swell. During the day our escort was completed by the arrival of the battleship ‘The Royal Sovereign’. One did not know either then or at any later date exactly what or how many naval craft were escorting us. We could see the ‘Sovereign’, always close in beside us, a destroyer or two a little way further off and, almost out of sight, our scouting corvettes, the signal lamps at their mastheads continuously winking at us and reassuring us that all was safe.

So life aboard went on peacefully day after day - parades, fatigues, (yes, a few). meals, sunbathing by day, the usual evening amusements plus concerts and a cinema and all aboard were deeply contented.

One night at about 8.30 pm we felt the concussion of depth charges exploding and wondered. But next morning no ship was missing from our convoy and no news was forthcoming re the explosions. Some days later we learned that our trusty destroyers had detected and had sunk an enemy submarine. This, so far as we could gather, was somewhere just off the Gold Coast, for a day or so later we steamed into Freetown, where we spent two or three uncomfortably hot and sticky days.

But ‘twas indeed good to see land once more after twelve days at sea. It was interesting to watch the antics of the native boys as they dextrously manoeuvred their frail boats, some laden with fruit, the majority containing but the owner, who left his craft unattended the while he dived under water to rescue coins thrown down from the decks. How they loved silver coins and what language they used (surely this could not have been learned from the missionaries!) when the silver coin turned out to be what they themselves called a ‘Glasgow tanner’, a halfpenny or a farthing wrapped in tinfoil. ‘No mo’ Glasgow tanner, please sah’.

Whence were we bound? We knew not tho’ rumour (afterwards proved correct) had it that our ultimate destination was Basra.

We were not sorry to steam out of Freetown and to exchange the fresh air out at sea for the hot sultriness of the harbour but for the evenings down below (for none other than the gun crews on duty and our submarine watch, was allowed on deck after ‘black-out’ time). Discomfort was to be expected, all port holes being tightly closed and screwed down but the ventilation system aboard the ‘Empress’ gave us comparative luxury. Just imagine steaming in the tropics under such conditions without a first-class air-conditioning system!

Two days after leaving Freetown we crossed the ‘line’ for the first time. I write ‘for the first time’ because we sailed round in circles for the next two days while ‘The Royal Sovereign’ left us and steamed away to assist ‘The Devonshire’ in hunting down successfully an enemy armed surface-raider.

Day after day passed uneventfully, hot sunny days and clear starry nights, little to watch by day unless it be the flying fish or schools of porpoise disporting themselves and the usual entertainment’s during evenings. We conjectured that our next stop would be either at Cape Town or at Durban and we could only guess at our course by watching the sun by day, none of us knowing sufficient of astronomy to be able to follow our course by night. Seventeen or eighteen days after leaving Freetown the temperature began to fall and, as it continued to fall the next day and we continued on our southerly course we thought we must be bound for the South Pole and not for Basra after all!

However, so far as one could gather, the next day we turned tail almost completely and started to steam due north. On the afternoon of the 18th December we steamed into the harbour of Durban, once more being greeted with brilliant sunshine and we looked forward to getting our feet on dry, steady land after thirty six days on the seas.

Hard luck, sir! All ships docked that afternoon barring the ‘Empress’ and you should have heard our amazed grumbles when, just after tea time, we started our turbines, turned around and put out to sea once more. There is a reason for all things, however, and we had left the harbour to escape an electric storm which was coming up and which might have endangered the ‘Empress’ had we have stayed in the harbour where there is, even at ordinary times, a heavy ground swell.

Next morning we put into Durban once more and got ashore at 2pm the same day. Oh the joy of being on land again (though I then knew why sailors rolled as they walked) amongst green trees and houses with many people in the streets, the ladies in cool, thin frocks and the majority of the males in white tropical suits, the shops showing everything and just the things one wanted (had one sufficient cash to buy).

Everyone had the same destination as a first call, the Post Office - cables and letters and cards to those whom we had left behind, though we were assured that no cable would be sent off for at least two weeks after we had left Durban. The afternoon flew by and dusk descended but, good heavens, no ‘black-out’ - every street light ablaze and no window shuttered! How different when we left England. Here, just once a fortnight, a ‘brown-out’ (that is a partial ‘black-out’ and has no bearing upon the colouring of the natives).

We spent the next two days very happily in and round about the city, much to see, many good things to eat (who, having been there, could ever forget those mixed fruit salads and ice cream without which no meal can be complete in Durban?) and how kind were the inhabitants or rather angels who went to endless trouble to ensure that the ‘boys’ had a really enjoyable time.

We were looking forward in eager anticipation to Sunday 21 st December on which day every inhabitant of Durban who owned a car was going to escort a party of tommies to see ‘the sights’. But, ‘twas not to be so far as we passengers on the ‘Empress’ were concerned. The bitter blow fell. We were ordered to change ship, not only to forgo all those enjoyments (and turkeys) which we knew would have been our lot on Xmas Day aboard the ‘Empress’ but, worse still, we had to move on Sunday 21st !

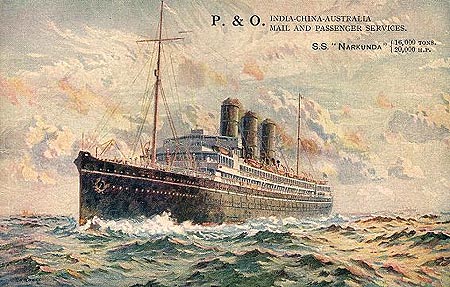

Talk about the Legion of the damned! We could not, I know have looked very happy as we marched in full kit and in the blazing sun some four miles round the docks to our next ship, the old ‘Narkunda’. Everyone said that this ship (a very poor relation to ‘The Empress of Japan’) had been withdrawn from service in 1926 - some fifteen years before - and I’ll say that on that Sunday when we first boarded her we did not look forward to spending Xmas Day. But why worry? We might have a very happy Xmas in the friendly atmosphere of Durban. We did get ashore after all on that Sunday but not until 6.30pm - too late, too late. We closed our ears to those who had been ashore all day.

Pleasantly passed two more days, 22nd and 23rd December but fate was still dogging us. On returning to ship on the night of the 23rd, tired but very happy, we learned that all further leave was cancelled as we were under sailing orders.

On the morning of December 24th we sailed - but wait! The old ‘Narkunda’ has lost an anchor and we return to dock for a new one to be fitted. There is just a chance that we may spend Xmas Day in Durban after all and surely the powers that be will not refuse us shore-leave on this one day of all the year. But luck is still not with us. Repairs have been effected too efficiently (for us) and we steam out after all on Xmas Eve.

Xmas Day on the Indian Ocean. We enjoyed ourselves of course but what might have been could not be erased from the minds of all the boys. Further days passed uneventfully and on December 30th we put into the Maldive Islands to pick up further orders, or so ‘those in the know’ said. Here it was that we came upon the real ‘blue lagoon’! A small island, or more probably a coral atoll, dotted with a few palm trees, semi-circular in shape, the sea on the inside being the most heavenly azure blue which beggars description. The setting being completed by the sand, which bordered the lagoon, a beautiful old gold in colour. One can never forget nor aptly describe that lagoon. Nearly two days were spent here, without being allowed ashore, and then once more on our way, escorted by the cruiser Exeter’.

On 8th December, long before reaching Durban, we had learned of the entry into the war of Japan and now we guessed that our destination had been changed to some station in the Far East. Rumour was rife -Singapore, Java, Bali (wishful thinking), I-long Kong and even Australia were mentioned. By this time we were once more ‘blacked-out’ at night but we were allowed to sleep on deck, under the stars.

It was between the Maldive Islands and Sumatra that I encountered a phenomenon, there is no other word for it. At 6pm one day, travelling so far as I could judge in a direction slightly east of south east, on the starboard side I had been leaning on the rail watching the sun gradually sinking down towards the horizon. Before the sun actually set, I had occasion to walk round to the port side and could hardly believe my eyes for there was the full moon, well up in the sky, shining across the sea. I pinched myself hard then ran back to the starboard side and there was the sun just beginning to set peacefully, turning the sky into that ruddy glow so well known in the East.

Our convoy crept along the Sumatran coast and turned into the Sunda Straits, between Sumatra and Java. So out went Australia and it was now odds on Batavia, main port of Java. Slowly we steamed through those rugged straits, where the mountains appear to come right down to the water, and constant watch was maintained for enemy aircraft. The old Narkunda’ fairly bristled with guns of all kinds - Bofors, Lewis, 3 inch, Anti-tank, Brens and what have you. Had they all been fired at one moment I think she must have been blown clean out of the water.

Java went out as we turned from the Sunda Straits towards Singapore.

Slow going through the islands and especially through the Banka Straits (which later proved to be a death trap for so many of our vessels in the retreat from Singapore).

After leaving the Straits we picked up more armed escorts, including a real iiak-ship’, until there were two escort vessels to every ship in the convoy. How safe we did feel then. Twisting and turning, slowly pursuing our course through the minefields to the south of Singapore, we came to within a mile of the docks. We had slowed almost to a stop, awaiting our turn to go in, when suddenly the heavens opened and down came the rain in sheets. But a few minutes later aeroplanes were heard up in the clouds and down came the bombs, falling into the sea between the docks and the convoy. We never knew for certain whether they were intended for us or for the shipping in the docks but, on this occasion, the ‘Nips’ (our most polite term for the Japanese) missed everything.

There followed a short pause before we entered Keppel Harbour and docked. And how we docked! At Pier 13 on the 13th day of January 1942 at 13.00 hours! Lady Luck was almost on our heels.

We disembarked at 3pm in pouring rain, but our discomfort was alleviated somewhat by the very cheerful New Zealand officer who met us and guided us to our billets. Speaking of the weather he said ‘It rains so hard and so often here that one gets used to being soaked to the skin, drying off without changing one’s clobber and getting soaked through all over again

Our Battery (anti-aircraft) drew lots with the other two Batteries of the Regiment - one to remain to take over part of the defences of the docks and Naval Base on Singapore Island, the other two to proceed up into Malaya to assist the troops at grips with the ‘Nips’. We drew the home game and stayed in Singapore.

Someone once called it the Gateway of the East and forgot to mention that it was the Tradesmen’s’ Entrance. Probably I saw the town at its worst under wartime conditions but I was not impressed by the squalor of the houses, the dirty streets smelling strongly of sour coconut oil (the one smell which I shall always associate with the Far East), the stinking ditches which run alongside so many of the streets and into which every bit of rubbish and waste is thrown and the general untidiness everywhere except for one small portion of the town where an attempt had been made at westernisation with clean modem buildings and wide streets.

Our first billets in Singapore were the Harbour Board Club - a spacious, any building which had been partly stripped to house expected refugees from Malaya. As it was still raining heavily we were glad to be in a dry billet and soon made ourselves comfortable.

Our neighbours were one of the Harbour Board employees, his wife and child and they endeared themselves to us by giving us tea, milk and sugar with which we made our first ‘brew’ on dry land after some nine weeks at sea.

This gift was the more welcome when our official rations did not arrive until 2am the next morning and this kindness made us feel that our coming from Malaya. As it was still raining heavily we were glad to be in a dry billet and soon made ourselves comfortable.

Our neighbours were one of the Harbour Board employees, his wife and child and they endeared themselves to us by giving us tea, milk and sugar with which we made our first ‘brew’ on dry land after some nine weeks at sea.

This gift was the more welcome when our official rations did not arrive until 2am the next morning and this kindness made us feel that our coming to Singapore was appreciated. But not for long. At 8pni on the day of our arrival a ‘gentleman’ with an Italian name rang up our O.C. and said that he was the Secretary of the Club and, moreover, that we were in the wrong billets. He added that he did not expect us to get out that evening owing to the torrential rain but he would have us vacate the premises by 8am the next morning. The O.C’s reply turned the wires blue and, needless to say, we did not move out for two or three days.

Our next billets were situated in a large camp in the jungle near the Naval base and we were comfortable here, although some ‘Nip’ planes did bomb the camp one morning using light bombs which did very little damage and caused no casualties.

About this time the enemy started daily raids on the town, usually not more than two per day but, as they bombed indiscriminately, using antipersonnel bombs, the casualties among the native population were fairly heavy. The ‘Nips’ sent over one, two or three formations of bombers, each one comprising twenty seven planes and all flying at height of approximately 27,000 feet. They were out of range of all ack-ack and, owing to the lack of modern aeroplanes on our side, they flew where they pleased. The few ‘Buffaloes’ which constituted the air defence of Singapore could not rise to such heights and some ‘Hurricanes’, which had come out from home with our convoy, could not be armed in time for the fray.

Meanwhile the enemy were advancing rapidly down Malaya and it was deduced that Sumatra and Java would probably be the next islands attacked. Our people could not afford to lose these islands while the defences of Singapore still held and a belated attempt was made to strengthen the defences of these two islands. Our Battery was ordered to Palembang, in Sumatra, near which were two fairly good aerodromes and we were attached to another ack-ack Regiment for defence of these.

We steamed out of Singapore at 5pm one afternoon towards the end of January, after spending an uncomfortable couple of hours ‘grounded’ while the docks were being bombed. Our small ship was so overcrowded that if more than half the number of persons aboard congregated on one side she started to list over and did the captain blaspheme, much to our amusement.

With us were two liners carrying refugees, mostly women and children, from Malaya and Singapore, and our sole escort was one destroyer. The next day at noon, as we were nearing the Banka Straits, we were spotted and bombed by a small formation of enemy bombers. They tried to hit the liners but our destroyer put up such a disconcerting barrage that no hits were made and the attempt failed. But there were still at least six hours of daylight remaining and we did not expect to reach the mouth of Mersing river, up which was Palembang, unitl dusk at the earliest. As we crawled through the Straits, we expected another attack at any moment but none came and we waved Goodbye and Good Luck to the liners as we turned into the mouth of the river.

Steaming slowly along, many insects buzzing around us (and not a few biting), thick jungle on either side of the river, the moon just rising and the air gradually cooling after the heat of the day, all seemed at peace. Our stay on this island was to be short, but a scant fifteen days, and during this time we fought strongly against mosquitoes. I always thought that mosquitoes troubled one only after dusk but here they worked 24 hours per day and raised some terrific bumps on us.

Here also we made our first real contact with bull-frogs, whose ‘singing’ carried far through the jungle and made the tropical night hideous with sound. We saw and heard all sorts of jungle animals including monkeys, baboons, gaily plumed parrots, parakeets, large butterflies, wild boar (one of these got into our sleeping quarters one night and caused some alarm in the darkness before removing itself), and one huge tiger! The latter, however, was a dead ‘un and lay on the railway line. Perhaps he committed suicide owing to boredom.

Nothing of note happened until Friday 13th February (again that number) when some 2,000 Jap paratroops were dropped near Palembang. Many of these were accounted for before reaching the ground and many enemy planes were shot down. One aerodrome was taken by the enemy and retaken by us on the same day. So rumours began to spread of many enemy forces coming up the river, paratroops dropping in large numbers round about, and large convoys heading for the island! Accordingly, when more paratroops dropped on the 15th, the order was given to evacuate and the nightmare journey to the southern coast began.

Apart from the O.C. and one other officer, two ‘batmen’ four drivers, six cooks etc and myself (detailed to travel with the Battery funds in the O.C.’s utility van) the rest of the unit left by train the same evening - the station being about 1 mile away. Halfway through the next morning the O.C. said that as he had just received orders to transport another officer (from a nearby air field) I must make my own way by train. So off I went, with one of our drivers, to the station to find out when the next train would be leaving. At the station the only porter still there said that there would be no more trains and he had orders to close up.

By good luck, three or four army trucks has been ‘left’ in the yard and we found one with the keys still in the ignition plus a full tank of petrol! What luck! We drove back to the camp and I asked the O.C. for leave to take the twelve cooks, camp staff etc with me in the truck, as no other transport was available. He agreed and within 30 minutes we had packed our bags and, unarmed except for one native machete, we were off and the nightmare journey to the southern port of Ousthaven began.

Wet, greasy tracks, in parts little wider than a car, up into the mountains, crossing rickety wooden bridges over deep ravines (in one place the bridge was no more than sheets of corrugated iron lying on poles), clouds of red dust which one could not avoid breathing in and intense heat during the day. Native troops at three different places tried to dissuade us from going ahead, telling us the paratroops had been dropped nearby in large numbers, but we continued on our way and met noone.

During the night we passed several oil wells which had been fired, red flames leaping many feet into the air and lighting our way for many miles. After 24 hours almost continuous travelling we reached the port of Ousthaven and what chaos as we approached the docks! Vehicles of all descriptions had been overturned into the marshes just off the road or left standing where the occupants had hurriedly alighted. Many luxurious private cars were there, some with packed trunks and suitcases still inside. As one lad remarked ‘The makings of a good Car Show’!

Our small party embarked within half an hour of arrival at the quay and as we went on board we saw a complete armoured unit, which had arrived from the Middle East and disembarked that morning, re-embarking. Too late, too late to help! Apart from the ack-ack Regiment and the R.A.F. personnel I have not heard since of any other units sent to Sumatra in time for any sort of defence action to be undertaken!

And so, on to Java. We disembarked at Tandjong Priok, main port for Batavia the capital, at 9am the next morning and went into Dutch barracks in that town. Meanwhile the rest of the Regiment were struggling down that awful 300 mile journey from Palembang to Ousthaven, making slow but sure progress with the guns. Imagine their feelings when they arrived at the docks some two days after we had left for Java only to be told that they could now destroy their guns as transport was not sufficient to remove them! They must have wept.

Java is a beautiful island, which the Dutch have taken great pains to make clean, healthy and attractive. Fine concrete auto roads between the large cities which themselves are well set out without overcrowding of buildings - the majority of which are very modern in construction. Everywhere we went we could not help noticing cleanliness and tidiness, especially among the natives - such a change from Singapore. It says much for the Dutch that although Java is bang on the Equator, mosquitoes are less in number than in any other equatorial region that we visited.

It was rather significant in view of what happened later that, as we disembarked, a Dutchman who was standing near the gangway said ‘You need not land here. We do not want you’ As is now history, less than three weeks later the Dutch capitulated. The ‘Japs’ had in fact been on the island for a month - we were not told!

Right up to the end we were well treated by the Dutch, both for accommodation and rations. The Dutch Army Quartermasters especially worked very hard to see that we always had plentiful supplies of all types of food on hand. When the Japs made landings however we found it very hard to get any information about the progress of the war on Java. In fact we did not know that landings had been made until we heard from one of our Troops which had been defending an aerodrome near the coast and had been forced to evacuate.

When we heard of the capitulation, we were on an aerodrome in the heart of the country. The two days previous had seen fairly heavy bombing and strafing by the enemy on this ‘drome and, on that day, we were expecting a ‘birthday’. Instead we ‘buried’ the Regiment and became a regular ‘Legion of the Lost’.

Not until March 28th 1942 did we move down to Tandjong Priok, near Batavia, entering there a large P.O.W. camp behind barbed wire.

Between 8th and 28th March we ‘lived’ up in the hills, by the roadside. ed We made native huts of sticks, rushes and banana leaves (the latter keeping out most of the heavy rains which fell from time to time) and augmented our British rations with such things as chickens, bananas, pineapples, bread, cakes etc purchased from native vendors who visited d us daily. One enterprising native built a stall near our ‘encampment’, placed half a dozen tables plus chairs by it and did a brisk business with the ‘prisoners’ in all sorts of refreshments. How he must have regretted our moving to Batavia! But no more than we did I am sure, for we spent twenty really happy and peaceful days there, making the most of our last contact with the outside world. Little did we know than that three and a half years would elapse before we should regain our freedom.

We entrained at 5am on the morning of the 28th March 1942 and arrived at Tandjong Priok P.O.W. Camp at 11pm the same day, very weary because we had marched, carrying our kit, the three miles or so between the station and the camp. There was little light from the moon that night and I well remember our party of 500 officers and men trying to see what sort of billets we were to live in, striking matches and groping about in the dim light of the night.

We quickly put down our ground sheets anywhere we could find room, rolled into a blanket and were soon asleep. Imagine our honor in the morning when we found that the huts had not been cleaned for years and saw hundreds of outsize cockroaches scuttling about the dirt encrusted walls and floors. The next two or three days were busily spent whitewashing and painting the interiors and exteriors, constructing beds from wood and sandbags and making rustic furniture.

The long huts were already subdivided into small rooms, not unlike stables, and each room had a sort of covered veranda in front of it with a low wall and a gateway opening onto the open space between the huts and the wire fence. Our O.C. inaugurated a competition, with prizes, for naming these little ‘homes’ and I remember that ‘The Wired Inn’ took the first prize.

Life in the camp was fairly peaceful with but little interference from the ‘Nips’. Altogether there were about 3,500 prisoners and the camp was divided into 13 sub-camps, each having its own wire fences. We were free to move about anywhere in camp, being of course forbidden to go outside the main fences. Needless to say, quite a few men used to crawl through the fences at night, walk half a mile down the road to a native village, purchase cakes, cigarettes, whisky and what-have-you from the natives and return.

One night a party of four had to wait for half an hour, lying in some long grass a few yards short of the wire fence, the while two ‘Nip’ guards conversed nearby. They held their breath when one walked towards them, paused, then trod right on one man’s back! Which were the more scared I know not but the ‘Nip’ apologised and told the Tommy to make haste and get back through the wire into camp!

For our news we had two wireless sets, one being hidden and held as a reserve. The other was built into the owner’s bed, under his pillow, and ran a 24 hour service. There were four expert operators, all of the Signals, and news in English was gathered mainly from London, Rome, Australia, New Delhi (India), San Francisco and Reuter. The ‘Nips’ suspected that we had a set in camp and once or twice nearly caught the operators at work. The owner had not hidden the set when he first came to the camp and, in fact, we had expressed surprise at his nerve when, a few months before, we saw him in a party of 300 march into camp with the set on his shoulder ! Always after that day if we wanted to bring anything into camp we remembered the rule ‘If you want to hide a thing from the ‘Nips’, carry it in your hand’ and it never failed.

Each morning each sub-camp had to supply so many men for outside working parties. Usually one did not go on these parties more than three or four times a week at the most, the work being mostly at the docks. Here one really toiled. Try, for instance, rolling a 50 gallon drum of oil or petrol 300 yards along a concrete road, then walk back to the warehouse and repeat the performance. Keep repeating it in the blazing sun with the temperature at 100C from 9am until 5pm with two rests of 15 minutes each, one in the morning and one in the afternoon, and an hour off at midday for a meal.

Other work on the docks consisted of loading scrap-iron onto a tramp steamer (incidentally, off-loading it again a few days later!), loading and unloading bombs of all sizes, cleaning out warehouses, loading 2 cwt sacks of salt and sacks of sugar onto barges etc.

Another daily ‘fatigue’ was at the Petrol Grave as it was known to us. The ‘Nips’ were making a petrol dump in the middle of a large coconut plantation. Here again, the work was fairly heavy, shifting and stacking petrol drums but there was plenty of shade and many opportunities (well used) of spiking the drums with a jack knife and smiling as the petrol ran out, to be speedily absorbed by the parched earth. One could also always bank on half and hour’s rest if a snake or scorpion was found, for most of the ‘Nip’ soldiers have childlike minds and delight in tormenting and being cruel to any animal, the more so if the animal is of the pet variety.

At Tandjong Priok the guards one day took a small monkey away from a native boy, attached a long metal chain to one of its legs then at odd intervals threw it up into a tree and pulled it down again. After a short while the monkey was suffering from a dislocated leg joint and the guards took no further interest in it. One of our boys asked for it and was allowed to keep it in his sub-camp. He was able, by massage, to restore the use of the leg and, until we left the camp, it was a great pet, albeit it most mischievous.

On another occasion, they imprisoned a dog in an old caisson, just outside the camp, blocked both ends up securely and left the poor animal to its fate. So far as we could gather from its howling, it died after the third day. As the caisson was near to a sentry’s post, we could do nothing but listen to its piteous cries.

There was ample opportunity in Tandjong Priok for keeping fit. Our ‘sports ground’ was large enough to contain a full-size soccer pitch with a fair space for spectators round the touchline. There was a soccer or rugby match usually four nights a week. There was a Dramatic Society which gave very able representations of Hamlet and The Merchant of Venice, amongst other plays; Debating Societies, Chess matches, Basket ball and, in fact, almost all forms of entertainment as well as Toc H, Y.M.C.A. etc.

We built our own little church of stone, wood and concrete, with a beautifully carved lectum and two magnificent stained glass windows.

The rations issued by the ‘Nips’ were fair, comprising for the most part, rice, flour, vegetables and regular supplies of meat and sugar. These were easily augmented by purchasing on working parties such commodities as duck-eggs (about Id each), cakes (3d each) sugar etc. We had a good camp canteen from which we could purchase, if supplies came in, eggs, sugar, cooking oil, margerine, jam, coffee, cocoa, tinned fish, our own corned beef, cigarettes and, just before we left, potatoes and chocolate.

Money was short in most cases, because the rates of pay for working parties was 10 cents per day (approx. 3d) for ordinary soldiers and junior N.C.O.’s and 15 cents per day for Sergeants and Warrant Officers. Commissioned officers received only one payment of money towards the end of our 7 months stay there.

On His Majesty’s birthday each sub-camp held its own special parade at l0am, ending with the National Anthem. All sub-camps synchronised in its singing, much to the concern of the ‘Nips’ who had not been warned of this parade and who thought that the whole camp was staging a joint escape. Orders were issued immediately that no future entertainments, parades or in fact any congregating of a body of men were to be held without the permission of the ‘Nips’.

On the whole the standard of health was fair, there being however many cases of dysentery, dengue (a form of fever), malaria and tropical ulcers. Bad cases were sent into Batavia to a Dutch hospital where able treatment was given by Dutch doctors under ‘Nip’ supervision.

There were many pigeons around the camp when we arrived and a number of these were enticed into one of the sub-camps and trapped. One or two soldiers who were fanciers bred quite a family from these, mostly for their own entertainment and in case they should prove of use later on. In September when a party of 500 officers and men left the camp for an unknown destination, two birds were smuggled away. One was released soon after embarkation to tell us that they had been joined by another party of 500 from other camps. The second bird was released, jf I remember rightly, six hours after the boat had sailed, with the message that Borneo was their probable destination. This turned out to be correct, as we found news of them in a paper nine months after our arrival in Japan.

On October 21St a further party of 500 left, again for an unknown destination, and as I formed one of this party my account turns from Java to the ‘Oshida Maru’, a Japanese cargo boat of about 3,000 tons which left Java on the morning of October 22nd bound for Singapore.

The previous afternoon our party had left camp and had marched 3½ miles, carrying kit, to the docks. In Java, the period between 2pm and 3pm is the hottest part of the day and is usually spent in siesta. Many men who could not complete the march were picked up by lorries and transported to the docks.

Little need be written of our journey to Singapore which took four days. We were confined to the two holds, both overcrowded and with the centre portion open to the sky. As it rained practically all night on three nights, we were not in very good condition when we reached Singapore. We spent a further 24 hours on board after docking, being allowed off ship once during the day for a very welcome shower under two hoses attached to fire hydrants. The next day we left the ‘Oshida Maru’ and spent some hours sitting on the dock side, after going through a form of delousing on a boat which the ‘Nips’ kept there for that purpose.

At 8pm that evening we embarked or rather were loaded onto the ‘Singapore Maru’ and 30 days of hell started. There were 1,009 British troops and three Javanese doctors squeezed into the bottom portions of the four holds, the upper portions accommodating some 1,000 ‘Nip’ soldiers. It was impossible to stretch out on the metal bottom of the ship; during the night one had to sleep with one’s knees tucked beneath the chin. I was in the forward hold which was at its widest part some 40 feet wide and about 60 feet in length, tapering sharply in to form the bows. 106 of us were squeezed in here, and after a few days, when it became necessary to set aside the bottom part of a hold at the stem for use as a hospital, a further 40 unfortunates were pushed in.

Once we had left Singapore we were allowed up on deck between sunrise and sunset, so that we did get a lot of sea air. Owing to the poor diet of steamed rice (poor quality) and stew, consisting of yams, small dried fish, meat, salt, sugar, plus what the ‘Nips’ thought was soup mix but which later turned out to be a fairly strong extract of yeast, many men had diarrhoea. There was no medicine for them and, in many cases, dysentery started.

We knew that the ship’s store contained many cases of our own tinned rations, such as milk, corned beef, Irish stew, cheese, tinned fruit etc and repeatedly the senior British officers on board approached the Nipponese officer in charge for a small issue of milk for the sick but this was refused. One issue of 5 small tins was made after about 50 men had died. In most cases the cause of death was heart failure due to general weakness and malnutrition.

When we landed at Moji on the island of Kyushu, Japan proper, we had lost 71 souls. Some 350 were left on board, too sick to be moved and although later these were moved to a nearby camp, only about 100 survived.

The night before we left the Singapore Maru, which had tied up alongside the quay, imagine our delight when we discovered that not one ‘Nip’ was left on board, every man-jack having gone ashore - presumably to celebrate their safe arrival home. The ship’s store was soon broken into and the majority of the canned goods, thousands of cigarettes, sacks of sugar and many bottles of sake (Japanese rice wine), were removed and shared around. That night was the only time any man went to sleep not feeling hungry, though few slept.

The next morning of course, as we had expected, the grand theft was discovered. The ‘Nips’ first threatened to shoot all of the officers, later saying that if all stolen goods still unconsumed were returned nothing more would be said. They realised, as we did, that any official enquiry would disclose the fact that they had left nearly 1,000 P.O.W.’s in complete control of a 6,000 ton cargo boat! They regained about two-thirds of what had been stolen and were only too thankful to leave it at that. Many of us left the ship with a considerable number of cigarettes and quite a few tins of food either stuffed in our shirts or concealed in our kits! And that after our kits and the ship had been almost turned inside out.

When we arrived in Japan proper, attired for the most part in shirt and shorts (tropical wear) we found it so cold that those of us who had blankets put them round us or shared them so far as was possible. We survivors were split into three groups and paraded on an open square on the dock side for a farcical Customs inspection. Those of us who had playing cards or packets of cigarettes had to declare them and they were formally stamped by the officials.

A bitter wind blew straight across the square and we stood there stamping our feet and trying to keep warm from 5pm until 8pm when a party of 170 of us were loaded onto a small barge and towed across the Inland Sea to the small port of Ube, which is situated at the South Western end of the main island of Japan - Honshu.

The journey in this open barge took about four hours. We almost crawled onto the quay when the barge stopped and learned immediately that our main work from that time on would be in a nearby large coal mine. We were too cold for that to have any significance and we were only too thankful to start what proved to be a walk of a few hundred yards to our new quarters (where many of us remained until peace).

Here a very pleasant surprise awaited us. The huts were new and clean, heated by charcoal braziers, and new blankets and quilts were already laid out upon the straw mats (Japanese version of bed). The ‘Nip’ military guards were very pleasant, many of them able to speak a little English and gave us sweet tea with a cigarette, a white bowl of steaming hot rice and stew and a loaf of bread. Having appeased our hunger (not a long job as so many of our fellows were sick and able to eat little or no food) we had a hot bath, the first for many, many days and so to bed.

After a fair night’s rest, those who were not still sick from the long sea voyage were required to attend a quick medical inspection after breakfast and then, as the day was bright and cold, we were issued with some quaint but warmer clothing. Each of us was given a long, remotely military style overcoat made from a rough, woollen, khaki coloured material and a pair of native canvas-top rubber soled boots so, thanks to our captors, we had at least something warm to wear over our ‘tropical kit’ during the winter.

The boots they issued were split-toed - each boot had a separate portion for the big toe - and most men felt comfortable in them. Unfortunately, by this time, I had contracted beri-beri and my feet and ankles were so swollen I could not get any size on. Fortunately I had acquired in Java a pair of Australian army leather boots as the issue pair I received when I joined as a volunteer in September 1941 were getting a bit past it and the extra pair issued in October, just prior to embarkation and (under orders) carefully dubbined at frequent intervals on the voyage, had been called in when we arrived in Singapore.

During the first two or three months we lost further members of the Regiment, mostly through dysentery or malaria. The remaining prisoners were, for the most part, treated kindly and allowed some exercise. Each day, for about an hour in the morning and again in the afternoon, all prisoners were escorted to a nearby open, grassy space where they were allowed to kick a football about and take general exercise.

The camp covered an area about 200 yards by 100 yards, enclosed by a wooden fence, close boarded, some 10 feet high. There was a ditch running round outside this fence and, in a number of places where the ground was not level, quite a gap could be seen between the fence and the ground, but few of us considered the possibility of escape. One might easily get out but, as the average prisoner was at least a foot taller than the average local inhabitant, the probability of further success outside was judged to be extremely remote.

Christmas Day 1942 was spent quietly and most of the discussions were on how long we might be here before the war ended. Knowing that the United States had come into the war after Pearl Harbour at the end of 1941, we mostly decided that, at worst, we might be free by December 1943.

At that time, December 1942, we were being fed reasonably and doing very little other than walking around and sitting in dry huts warmed by coal stoves, and life could have been much worse. Talk about innocents abroad!

On January 1st and 2nd we were taken in small groups on a visit to a local coal mine about half a mile from the camp. As very few of us had ever been near a mine, the chance of actually going down one was, to most of us, attractive. And so it was - the mine was on two levels below the ground (and, as we found out later on, below the Inland Sea!).

It was an interesting experience and almost enjoyable until we got back to camp. While discussing what we had seen one chap, who had been a miner in Wales before being called up, said ‘You know why we have been shown that mine? I bet most of us will be working down there within a couple of weeks’. And so it turned out.

At the start, the fit chaps, excluding the officers who, under the Geneva Convention could not be forced, to work, went down the mine twice a week for a shift of 5-6 hours when they were shown how to use picks Led by the Japanese miners, each ‘gang’ would eventually arrive at a remote coal face where we were to work that day and hopefully (from the Japanese point of view) despatch a specified number of wagons filled with coal to the surface. To most of us, of course, the work involved, in battering away at a wall of coal, usually 6-8 feet high and varying in width from 6-20 feet, was much harder than any we had previously experienced.

If we were working a ‘soft’ face, using picks and shovels, the shift was comparatively easy, once our muscles had got used to the labouring. If the coal was really hard we had to adopt a different method. When one got the knack of using a pick it was possible to bash away at the coal face and, after 15-20 minutes, finish up with enough small splinters to fill a couple of pails. This usually produced a lot of wailing and tut-tutting from one of the Japanese miners who then showed us how it should be done.

The more interesting work was opening up a new heading. Usually a Japanese night shift would cut an opening - about 10 feet wide by 4-6 feet deep - and our job was to further their work by cutting in deeper, using explosives to loosen the face. We worked in groups of four - one holding the body of the drill on his head, two more taking the weight at the sides and the fourth man pushing and guiding the 3-4 foot metal drill onto the face and controlling its running by electricity. Of course we changed and changed about while we were making holes in the coal face - the number of holes depending on the size of the area to be blown down.

Having finished drilling we would push a charge into each hole, plug each hold up with clay or similar, run out the necessary wires (attached to each charge) back to the entrance, connect up to the firing plunger and depress. After a few minutes, to be certain that all loose coal had dropped and that all the smoke and dust had cleared, we went back in, always preceded by our Japanese miner-in-charge, to load up the coal blown out. In most cases we considered that the extra effort of drilling was worth it.

All of us moved and worked in slow motion, but we could move as fast as the locals if danger was approaching. Sometimes when we were working in a part of the mine where, because of the strata, the seam was going up hill, we suddenly heard a rushing sound, coming from the railway lines further up the hill and realised some full coal tubs, usually securely clamped to the moving wire rope which ran from the pit head through to the workings, had got away and were soon to pass us (if they stayed on the rails) and smash things up a bit when they eventually jumped the rails on a bend a few hundred yards further down. It never occurred to us that our way out might be blocked!

Only twice was our gang put to work in headings where there was a danger of roof falls of rock or coal. In one case there seemed to be little coal among the rock walls and what was there was so hard and brittle that, after half a shift, the Japanese decided that the output was not worth the effort and we moved.

On another occasion we were warned that the coal face was not very safe so some worked while others stood watch. I was one of those picking away at the face when there was a sudden shout that the whole face was falling! We all turned to jump back to safety but a large piece of coal trapped my left foot. Two other men quickly released me and pulled me back from where a piece of the coal face about 15 feet wide by 6 feet deep had fallen outwards in one piece. In no time the Japanese had us out of the heading and into a safe place. There they found that I was bleeding from a gash over one eye although I could not feel any aching. In a very short time I was sent, with towels round my head so that I could not see, back to the pit head. I can still remember that walk of about half an hour, bent almost double in places where the roof beams were low and holding onto the back of the belt of my friend who was leading me back to the top. When we reached the pit head two armend guards from the camp were awaiting our arrival and we were taken back to camp where our doctors had been notified of the accident and were in readiness.

Our American Naval doctor put me on a bed under one of the windows in the hospital section and, with our two Japanese guards looking in from the outside, he started to clean up my head. After a short while he said that the cut over the eye was not too bad and that two stitches should suffice which would not leave much of a scar. For a while he continued removing small pieces of coal and rock from the wound and then said that I could open my eyes before the put in the stitches. I could no longer see the two guards at the window and when the doctor stepped to the window and looked out he found they had fainted!

As a result of this accident I was off mining duty for some weeks and spent two weeks or so in the camp hospital before being returned to ‘light’ camp duties. The Medical Officer insisted on my wearing much bandaging on the head, mainly to put off my return to the mining brigade for as long as possible. This worked quite successfully for some five or six weeks when the threatened visit of a ‘proper’ Japanese doctor ‘in a few days’ precipitated my return to the mine.

Light camp duties consisted of helping out about the camp, keeping it clean (picking up paper, cleaning windows and sundry sanitary duties -including pulling a large wooden tank on wheels twice a day to the local ‘lake’ to get rid of excess ‘matters’. After a week or so on these duties, one moved up to the timber yard which was adjacent to the pit head.

Here about six of us spent most of the day stacking and re-stacking props, most of them from 6-9 feet in length and usually about 9-12 inches in diameter. The wood was mostly one of the pines interspersed with some wood that looked like ash or sycamore. To shift each piece required guessing where the centre point was, having regard to the overall thickness and shape, then bending forward to put one’s shoulder under this central point, pulling the log onto the shoulder and resuming the upright position at the same time. One then walked off with the log precariously balanced to wherever the ‘yard boss’ desired.

The Japanese boss was, to say the least, elderly (we guessed at well past 60) but, in his way, one of Nature’s gentlemen. He never shouted, usually smiled and did not drive us. He had a small grandson of 5 or 6 years old who often paid visits and was so smiling that his efforts to use English were much and successfully advanced during the day. So we spent a few peaceful and almost happy hours in the fresh air. The only times we moved about more quickly were on the few occasions that the old man saw military approaching. He would tell us to hurry about and we were happy to oblige.

Before I was returned to the mines I had a few days in the Cook House, to replace one of the regulars who was sick. The food, mainly just rice, was cooked in four large iron vats over wood fires so that when the rice in the water had boiled enough, the fires could be withdrawn and the rice continued to finish cooking with the heat of the cooking iron vats. Although a high standard of hygiene and care was maintained, cockroaches were a menace. On one occasion I was on late duty, to provide cooked rice for the late shift returning from the mine at about 9pm and I went to the Cook House at about 8.45pm. As I switched on the electric lights there was a sudden noise, like gravel being tipped out of a lorry. Quick ‘though I was, I saw only the tail end of, as it seemed, hundreds of cockroaches, running for shelter. Within a couple of seconds or so, all was quiet - not a cockroach in sight!

My tour of duty in the Cook House did not last long, thanks to being inquisitive. One afternoon the Japanese gave us a load of sweet potatoes. The cooks decided to boil these for the troops but I wondered whether they could be baked. So, with two other ‘cooks’ we put about 6 sweet potatoes in the hot ashes of one of the fires, covered them up and went off duty. When we came back on the next shift a small storm broke. The whole Cook House staff were lined up and told by the Officer-in-Charge, Cook House, that the potatoes had been found by a Japanese guard during our off duty period. He had been appeased by a plea of ‘they must have been carelessly dropped’ but the C.O. (cooks) wanted details and I had to leave my cushy number in the Cook House and resumed work in the mine the next day.

Our rest days, when none of us went to the coal mine were little havens of peace when we could renew acquaintance with friends from the same Regiment or pass an hour or two with new friends in the camp. Or we would be cleaning and mending our clothes - we were allowed access to our personal ‘kit bags’ once a month to change items and there could be no departure from this Japanese imposed rule.

I often thought in later years that this enforced labour down the mine not only strengthened basically one’s physical constitution but also helped us mentally in our resolve to survive. After two years in captivity most of us were mentally reduced to thinking only of one day at a time and I could not remember much that had happened in the years just prior to the outbreak of war and, like most, had long since stopped trying to forecast when we would be free.

Half way through 1944 two events occurred which boosted our hopes of freedom. The first was an alteration to our mining shifts, instead of having each seventh day as a rest day, we were made to do twelve days and allowed to rest on the thirteenth. In the months that followed the number of days worked without a break increased gradually until we reached a total of 26 consecutive days worked before we were allowed a rest day. Although this was very hard, we came to the conclusion that it could be because the events of war were beginning to turn in our favour.

Then our little miracle happened! As some of our miners were walking back to the pit head at the finish of a shift, they were passed by a small party of Japanese miners going the other way. This was not in itself unusual but, as the last one approached our gang he fell behind a bit and as our men passed said quietly ‘Hi-ya boys’ with a marked American accent. Our men quickly agreed to say nothing of the event to anybody except the British C.O. so, with everybody maintaining secrecy, events quietly developed and the following details emerged. The miner had in fact been living in the United States and was on a visit to his parents in Japan when war broke out and he had to stay. As an engineer he opted to work in the coal mine rather than join one of the Services.

On later occasions he told some of our men that he would pass over a news-sheet to one of our gangs during a shift and we would arrange to get it back to the camp. The ‘paper’ was just two pages - 4 sides - and was in English! The choice of English was apparently because the paper was produced for the benefit of a fair sized German community which had been evacuated with certain valuable technical data etc about the photographic and telescopic industry. They could not read Japanese but English was alright. How lucky can you get?

Getting the papers back to camp was regarded as a necessary chore generally but at times it could be a bit nerve wracking for the person elected to do the carrying. One had to remember that we were always met on arrival at the pit head by two military guards and marched back to camp where we formed up into three ranks and were searched. In the beginning the paper was folded into a small size then carried in the sleeve or in the mining cap. After a while this was thought a bit risky and a routine of rapid line changing was developed. Thanks to some pretty quick footwork either the carrier would move unnoticed from the second line to the front which had just been searched, or the small parcel only would be transferred by hand.

We had been warned by our newspaper supplier that the news of sea battles etc was correct as to time and place but results and losses needed to be transferred from one side to the other. So a feeling of life and hope began to come back. We learned of Allied forces progressing slowly across the Pacific and, after some months, in the clear blue skies above our camp we could see the smoke trails of U.S. planes and sometimes be able to recognise Flying Fortresses flying much to high to be reached.

After the first few months of 1945 we noticed a different outlook from the Japanese miners and we began to hear air-raid sirens, mainly at night. The main objective of the U.S. bombers was the industrial town of Ube which was only about ¼ mile away from our camp. The raids were usually to drop ‘fire-bombs’ which caused a lot of damage in the town where most of the buildings were of timber. The guards always hurried us from our camp to ‘dug outs’ in the sandy shore of the Inland Sea and back again when the all-clear sounded.

On some occasions we were ‘allowed’ to go down the mine on the day following a raid but, usually, there was no apparent worsening in our treatment from the Japanese miners although we did hear of some ill treatment of Chinese prisoners - also being used in the mine - at the hands of the Japanese from Formosa.

However, during June and July 1945, as the Allied navies were obviously advancing across the Pacific towards Japan, the Japanese miners were chattering more to each other when they passed in the mine than on previous occasions and we noticed, in camp, a difference in approach, a general tightening up, especially after a new Japanese Commandant appeared. Usually their tours of duty varied between 6 months and a year although, on one occasion when we had a Commandant who was friendly, with perfect English, (he had spent 3 or 4 years at Oxford University), he was removed after 3 months.

Sometime in mid July 1945 we were told that we were to be given a swimming pool in the camp for our use but we must make it ourselves. So we had to dig a hole roughly 60 feet long by 25 feet wide and about 6 feet in depth. Digging commenced and went on sporadically , mainly because the only labourers were the British miners who could dig only on their free days or rest days which were being allowed less often. Of course we were aware of the probable use to which this ‘pool’ would be put if the Allies invaded the Japanese mainland and, in this sense, much relief was felt by all when the first atomic bomb was dropped on 6th August 1945.

When we went to the coal mine the next day the excitement and nervous state of the Japanese miners was very apparent - much chattering and arm waving accompanied by ‘bomb’ noises. It was not until some two months later, when we were free and on our way to the Philippines, that we learned that two atomic bombs had been dropped - the first on 6th August at Hiroshima, 100 miles or so to our east and the second a few days later on Nagasaki, over 200 miles to our south west. We saw an official U.S. account of the second bomb which said that the primary target was to be Ube, (only 1/4 mile from our camp!) but, owing to misty conditions, it had to be dropped on the secondary target, Nagasaki. At long last the general feeling in the camp was that the end of the war was very near. The Japanese Commandant was approached by the senior British officer in the camp and asked to state whether or not the war was over. He would not confirm this and so, on the next morning, he was given 24 hours to ascertain the position.

At 12 noon on the following day the British O.C. asked him again whether the war was over. Again there was no answer. The British O.C. returned and a prearranged plan was put into action. A British officer and a guard of 6 soldiers marched across the parade ground to the Japanese guard room, marched straight inside and evicted the Japanese soldiers, having taken their rifles from them. So now we were sure that at last we were free. Surprisingly there were no loud shouts or other signs of rejoicing, just a quiet feeling of peaceful relaxation.

Within a day or so we had a visit from a Swiss official, probably a diplomat, who supplied a radio or radiotelephone through which we received instructions over the next few weeks. The first was to put crosses of white material on the roofs of our huts so that the U.S. Air Force could find us to drop supplies - medical, food, clothing etc. We discovered, before any drops occurred, that some weeks previously some Canadian Red Cross parcels had been received at the camp, unbeknown to us, and had been hidden in the coal mine! These were recovered quickly and so it was that we had our first freedom celebrations in the issue to each prisoner of not one but two Red Cross parcels.

Other Canadian Red Cross parcels that we should have received during our time in camp were, we think, appropriated by the Japanese for, during our time there we received only one delivery early in 1944 of about 20 parcels (divided between over 200 men), followed by another issue’ almost a year later with 6 men sharing each parcel.

Our doctor, U.S. Navy, called us together for a few advisory words about the new parcels. He said that when supplies were dropped food would be plentiful but to remember that over the past 2½ years or so in camp meagre rations would have resulted in smaller stomachs. We were advised to take it easy and not to rush to fill our insides or we could do damage. Thanks to him, only half a dozen or so out of around 250 men suffered, albeit for only two or three days.

What happened to the Japanese soldiers who were disarmed and turned out? Just opposite the main gates of the camp was a small fish shop and, as we wandered in and out at will as the gates were always open, these Japanese guards sat on the empty shop shelves and watched us!

In regard to the dropping of supplies we made certain that, so far as possible, anything found was to be brought to the camp. Our good friend, who had supplied us with newspapers, was the official appointed Head Man of the district and he issued orders accordingly. On one occasion two old fishermen turned up with a large carton of very soggy cigarettes. We showed our thanks with a friendly present of several tins of food. As for clothing, there was still much left after each of us had been supplied with three complete sets of clothing and boots.

The way in which the supplies were dropped was awesome. Two fifty gallon oil drums welded together, filled with goodies, a parachute attached to two handles welded onto the drums and out she goes! On a few occasions the ‘chutes immediately separated the handles from the drums which then rushed clown to earth. It was quite alarming to see a parachute with drums attached snaking down towards one, even though they still had some hundred feet to fall. It was said that more of the local inhabitants were killed or injured by these drops than from any bombing that had previously taken place.

Our peaceful rehabilitation and return to a normal way of life continued in summery weather - much the same as we had been accustomed to before 1939.

One day, a friend who also came from Oxford heard that there was another P.O.W. camp close to the railway station about 9 miles away and suggested we might try to visit it. He had a note of the place so, the next morning, we went to the local station, found an official in uniform and asked when the next train would be going to the other station. To our delight he said that the next train , due any moment, would stop at the station we required. When the train arrived, after a very short time, he directed the two of us to follow him. As the train stopped we saw that every compartment was full of people sitting or standing and others were on the roof or clinging to the outside handles. The Station Master opened one door and, after ordering everybody out, he bowed the two of us inside then securely locked both doors saying that the station we required would be the third stop when we would be let out.

So we settled down to enjoy our journey in comfort and, as promised, at the third stop our compartment was unlocked ,we were ushered out, directed to the camp we sought and told that the next train ‘home’ was due in one hour’s time. We soon found the other camp and therein several soldiers of our regiment. They were very surprised to see us and, while we were glad to see them, we were amazed that, although they had heard that war was over, none had yet been outside their camp!

As arranged, we caught the next train back to Ube, our station, riding as before alone, in state, in our locked compartment. So life, in what was now more like a holiday camp, meandered on until early September 1945 when we started our long journey home from our local, friendly railway station.

We were not allowed to pass through Hiroshima, which was on our direct route, so the train made a detour which resulted in our journey lasting for over 14 hours until we arrived at the port of Wakayama. As the train pulled into the station and stopped we were greeted by U.S. troops fully-armed and by two British officers who had just arrived after a 2½ day flying journey from the U.K. Then we were all taken for medical checks and a change of clothes - we all finished up in U.S. Navy gear - then on to a small U.S. hospital ship at anchor in the harbour. In this piece of Heaven, we spent our final night in Japan.

Imagine our delight to find that we were to sleep in proper beds with pillows and sheets - the first time I had experienced such a thing since leaving home in Oxford to join the Army as a volunteer on 5th September 1941 - near enough 4 years before.

No one found difficulty in sleeping that night and, the next morning, we found that the ship was still tied up alongside the jetty. At breakfast we asked where several of the crew were, to whom we had spoken the evening before. The answer was that most of those missing were off-duty - well in fact they were off-duty sea sick and we had not even sailed!

We did in fact sail later that day and, in the afternoon, we were transferred to a small U.S. troop carrier but, on finding that our sleeping places were flat wire bunks fixed to metal poles - I was directed to the tenth one up one pole - my Oxford friend and I decided to sleep on deck and did so for 4½ days until we arrived at the Philippines. Here we were based in a U.S. camp on top of the cliffs - back in Heaven once more!

Our U.S. Army hosts were determined that we should reap the full benefits - in mind and body - from our 3 weeks stay in the Philippines. For the first week we were ordered to rest in our tents from 1pm until 4pm each day, ‘bunk fatigue’ in their terms, thereafter we passed each day in a peaceful, albeit lazy manner.

The weather was almost perfect, sunny but not too hot and usually a gentle cooling cliff top breeze. After rising, a gentle amble a few hundred yards to the main camp found us at the eating place. After a good breakfast we could walk around the camp and chat (to whoever would lend an ear) until the one daily parade which we were not allowed to miss - at the equivalent of the U.S. P.X. store, somewhat similar to the British N.A.A.F.I. - where we could ask for whatever we wished within reason. Chocolate an other sweets, cigarettes, cans of Coke etc and all for free! Even, if we might have had money we would not have been allowed to pay.

On one occasion, as we strolled round the camp, my friend said he could hear people hitting a ball against a wall. As he had been a tennis and racquets professional at an English Public School before 1939, he just had to see what was happening. We discovered a few U.S. soldiers doing just what he had heard - trying to hit a ball against the wall of a derelict building some yards away and to continue volleying the ball as long as possible. There were three groups playing thus but, as few men managed more than three hits before a miss, my friend started to fidget. In the end he just had to ask if he might have a turn and a racquet and ball were handed to him with the smiling comment ‘It’s not as easy as you think’.

My friend bounced the ball once or twice and then started to hit it against the wall. Three minutes later, after he had played forehand and backhand shots without a miss, he stopped and handed the racquet back to a G.I. with a Thanks, I enjoyed that’. What he did not know was that, for most of the time, he had been the only one playing - to a very appreciative crowd of onlookers!

So we passed three weeks in peaceful living, coming slowly to terms with life again. During our third week we all had our most enjoyable surprise so far - letters from home. For most of us these were the first letters we had since leaving England in November 1941, almost 4 years before. During our imprisonment in Japan - some 2 years and 9 months -we were told on three occasions that letters had arrived from home but often a month would go by before a few letters were given out to a few men. This was just part of the mental treatments that we grew used to -news that letters or Red Cross parcels had arrived and then the wait which, in the case of a letter, could be up to three months, before a few were handed out. Many of us did not get our letters even then.

Finally, in the Philippines, I was overjoyed to get a letter from my wife and to know that she was well. Naturally, each of us had worried about the loved ones we left behind in the U.K. - they had already experienced air-raids, bombs and shortages of food and other things before we were parted in 1941 and we knew that conditions had not improved thereafter. All of us had prayed, in our own ways to our respective Gods, nightly to ask that they should be kept safe and that, one day, we might be reunited. We were able to reply to these latest letters immediately and knew that this time our letters would be posted.

After this three weeks of happy and peaceful rehabilitation we heard that we were to leave for Canada - and on a British aircraft carrier! Within a day or so we were on H.M.S. Glory - a carrier from which the aircraft had been removed - en route for Canada. Two of us found the sea air so refreshing that, once again, we persuaded one of the crew to find us a small mattress apiece which we laid on the deck under cover in a recess just inside a door way and we crossed the Pacific sleeping peacefully at night. After nearly 3 years sleeping on a mat at ground level we were well suited to this type of bed and most grateful to our Navy.

Each morning it was another touch of magic to step out, at first light, onto the outside deck to see the usually calm waters of the Pacific. The captain of H.M.S. Glory often altered course at least once each day because of spot of turbulence ahead that, as he put it, he thought we could do without! Usually we seemed to be the only ship on the ocean as far as we could see and, when we crossed the International Date Line we, and the whole ship’s company, had a day off. Having sailed across the l80 degree line in a westerly direction, the day before and the day after only counted as one. Most confusing!

A few days later when we emerged on deck at about 5am, we had our first sight of America - one or two giant mountains with magical peaks pushing up into the early sunshine - a truly wonderful sight. Was it the Olympic Mountains that we saw?

We proceeded up the West coast, and docked at a naval base near Vancouver Island. This was a very moving moment as the first men ashore were wounded Canadians. A large crowd had gathered to welcome them home and we Brits on board, still thousands of miles from home, cheered them to the echo.

We were soon disembarked and were welcomed to our ‘home’ for the next three weeks in the barracks of Princess Patricia’s Royal Rifle Corps. Much of the first week was taken up by further medical examinations which, although fortunately they did not show more than that we were getting pretty fit again, nevertheless made us continue with our slow return to a normal, healthy life.

We were able to explore Victoria, the capital city of Vancouver Island, and greatly enjoyed their wonderful parks. It was also our chance to find the answer to a question that one of our friends had posed during our voyage across the Pacific.

Were we still sane or were we in fact perhaps mad’? Having been so long together how could we tell? After chatting to some of the sailors on the H.M.S. Glory we decided that we were much the same as the crew and therefore sane. Unless of course they were as mad as us, having been shut up together for so long on the Glory. Happily, after wandering about Victoria and speaking to a number of the residents - of all ages -we decided we were definitely sane.

During our second week at the barracks, the Canadian authorities took notice of our penniless plight and very kindly gave each of us 5 Canadian dollars to spend. I do not know what the sterling equivalent of $5 was at that time - October 1945 - but I did see a Rolex wrist watch in a jeweller’s window priced at $4.40. We were made so welcome during our stay, both by the military authorities (who put on two separate variety shows at the local theatre especially for us) and by the local residents, that our stay came to an end almost too soon for us. But only almost for we all wanted to be home for Christmas, having spent the previous 4 Christmases ‘on active service’ and we still had over 6,000 miles to travel.

On about 6th November 1945 we caught the ferry from Vancouver Island over to Vancouver on the mainland and, in the early evening, we embarked on a Canadian train for yet another ‘Journey of a lifetime’ across the North American continent on a journey of 4½ days to New York.

When we joined the train we were told that at about 3.30pm the next morning we would be stopping in Medicine Hat to be welcomed there by some members of the Canadian Red Cross who would provide us with refreshments and the chance to send a card home. So, early the next morning, most of us got up, dressed in our uniforms including great coats (for we had been warned that the temperature would be about 30 below) and stepped out on to the platform. About 30 ladies of the Red Cross made us very welcome, plying us with hot coffee and biscuits and postcards for our messages home. At last we were able to give them our heartfelt thanks for the Canadian Red Cross parcels, the only ones that we had received in Japan.